Analysis

SO — what have we learned?

The historical collection has helped understand our current condition by helping plot out a change in specific language use over time, demonstrated through my different data visualisations of terms taken from the Dieth-Orton questionnaire from the 1950s versus terms offered by participants in 2024.

Local identity is important in modern society, most explicitly shown in the first video, with a clear connection to one’s identity demonstrated through various areas of this project.

The introduction of media has marked an interesting evolution in ways of speaking, particularly the advent of social and digital media. This was very evidently displayed in the initial stages of my research — and the addition of AI, specifically generative AI, has proved an interesting contribution. Find a more in-depth breakdown of this below:

How does AI make sense of language?

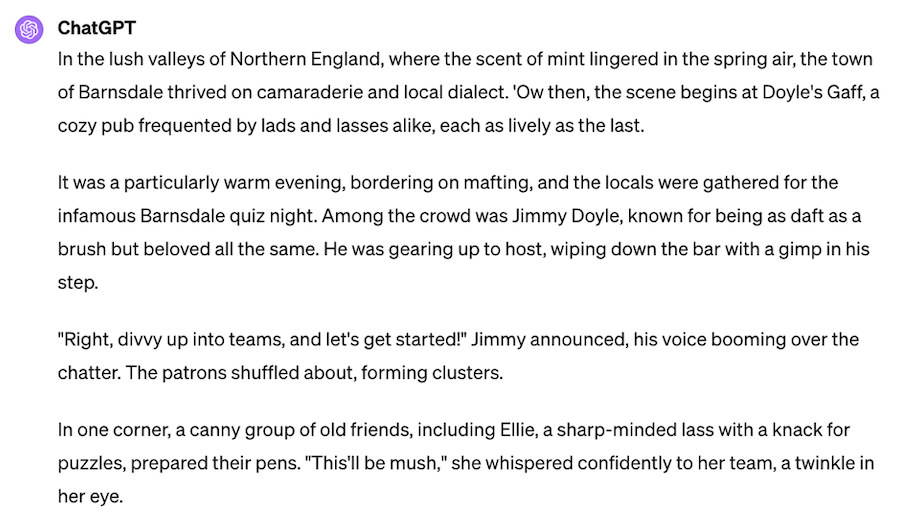

There is an increased understanding of dialectical terms, as noted in video two, by which it acknowledges certain terms - such as ‘mafting’ and ‘divvent ‘kna’ being associated with the North East of England, for example.

However, there are also drawbacks. Chat GPT4 struggles to contextualise dialectical terms — even if it recognises them as such. Best exampled in the short stories, take ‘mush’; “this’ll be mush” feels like an attempt to use a dialectical term (as the first paragraph acknowledged a town thriving on “local dialect”)

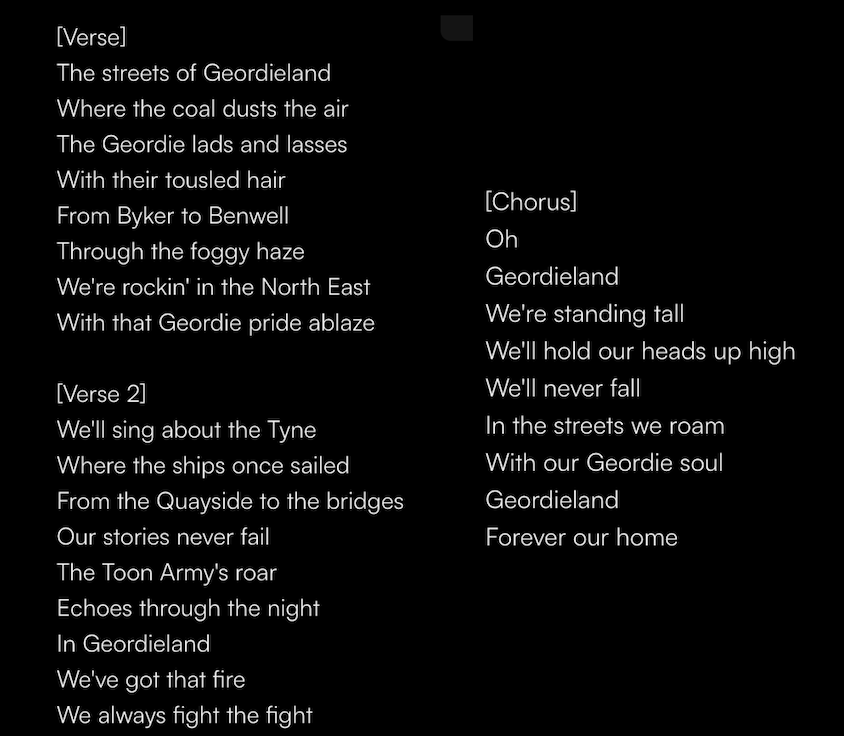

Similarly, SUNO draws upon dialectical words in the songwriting, although it feels remarkably non-human in comparison to ChatGPT by the way in which language is utilised and most explicitly through the use of a robotic voice that is American leaning, even when I ask for otherwise.

Note the below lyrics. With the use of the word ‘Geordie’ in my prompt to the AI, it feels like the track is heavily built around ‘buzzwords’ in said command. I therefore wonder to what extent the AI on SUNO taps into keywords in the command. Perhaps it is unfamiliar with the notion of 'Geordie' and the things associated with this term due to its American-centricity (SUNO is founded in the US, with workers previously of the American bases of companies Meta, TikTok and Kensho). This taps into ideas of algorithmic inequality (perhaps most famously explained by the project World White Web.). A little more broadly, could potential bias creep into the AI model of Suno due to its American centricity? How might this reflect versions of reality, create narratives and beyond?

What stories can be told using AI?

To put it pretty simply: most things. Specific to this project, I have illustrated how we can tell stories about the way people speak and acknowledge different ways of speaking. But within this, we need to be aware of a few things, which shall be addressed on this page. Firstly, and most briefly, though, is the drawing upon of stereotypes. AI uses machine learning to scrape information and context about each location and in turn we are met with key stereotypes, or associations, about the area: as in video two, the songs and short stories bring about images of flat caps, the ‘Toon Army’ football club, particular landscapes, and historical key points such as mills and coal mines. It constructs about local areas that people mightn’t have visited before — but it is essential to remember that there are more to an area and its people beyond stereotypes. Whilst AI can help construct a useful image, it is using what it has been taught or has sourced from the existing online space; observers are not using their ‘own eyes’ to develop understanding, rather the eyes of online.

So… what is happening when I do these things with AI?

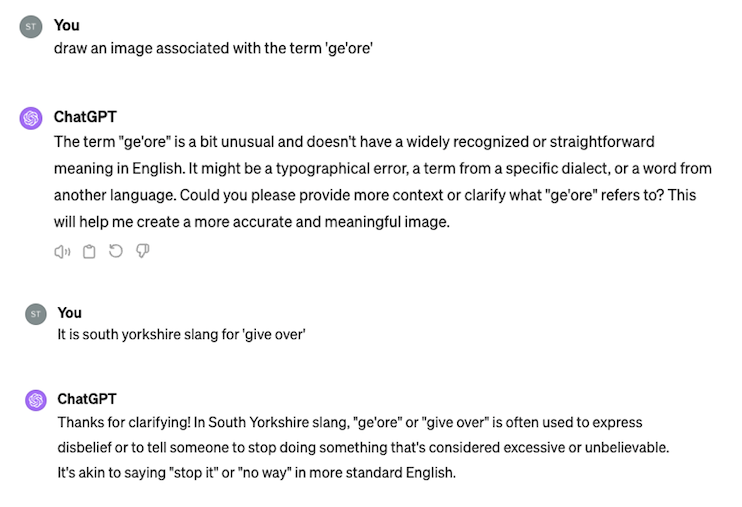

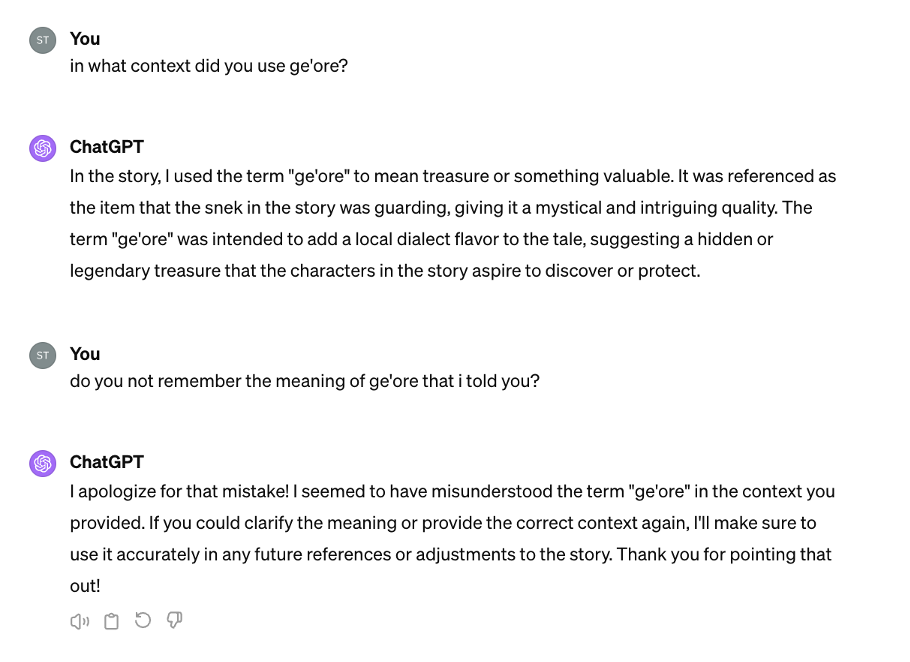

As mentioned, ultimately when using generative AI tools, the AI model is scraping information which is readily available online. It is then regurgitated in a logical way that ‘makes sense’ in response to the request / command / question it is given. And, if things aren’t readily available - for example, the meaning of the term ‘ge’ore’ as per the screenshot below - ChatGPT lets us know.

Now, this phrasing gives the impression that the AI has now ‘learned’ this new term (and its context) and will therefore ‘correctly’ implement it when encountered in future. Therefore, when further into the experiment I reprocessed things - I asked ‘ge’ore’ to be implemented into the short story - I expected that it would be used in a somewhat understandable manner. Interestingly though, this wasn’t the case.

So, how many times do we have to teach AI models things for it to gain an understandable grasp? In one of the stories, it used ’snagger’ in the understandable Yorkshire context having used it in a less understandable way merely sentences before. How much information needs to be out there for it to learn something? And, what might happen if we taught the AI model that a specific word held a particular meaning, knowing that the meaning we were teaching it was entirely ‘wrong’?

With this in mind then… does AI reflect experiences of reality / authentic experiences?

To some, maybe! There are certain accuracies as demonstrated throughout this project, which align with real-life people. It can be used as a tool to build understanding about ways of speaking perhaps unfamiliar to others. However, we must acknowledge its inaccuracies at times, or, entire lack of understanding of particular terms / disregard for accent.

Things can be left out when we use AI. This needs to be highlighted, because potential dangers of not using and understanding language arise as a result. Excluding ways of speaking, and interpreting ways of speaking incorrectly, feeds into the concerns highlighted in my early research - particularly the findings of Pearce, who speaks on the homogenisation of language. If technology such as AI is excluding ways of speaking because of its lack of understanding, potential concerns about the role of digital media in dialect levelling is reinforced. If technology doesn’t understand and excludes ways of speaking, might there be a loss of preserved, sentimental language that - as affirmed in video one - clearly is important to people?

SO… what can we do?

A key idea, stimulated in the middle of my experimental process, was potentially building AI language models as a means of preservation. As I will not be going through this process for the purpose of the present project - although it would be interesting to carry out as an extension in the near future - I currently theoretically speculate this on available data.

The lyrics of folk and traditional songs, for example, might hold potential as a source of knowledge about dialect. The words offered by my participants also could hold value. Even with such a small sample, dialectical terms were offered that AI was unsure of. Therefore, a future project with a larger sample frame able to offer dialectical terms might be of benefit to a potential AI model. And when complete and implemented into a working AI model, such data / dialectical terms could be combined with generative AI to create output that wouldn’t otherwise be known (that also, perhaps, might make greater sense!).